Spanning 82 seasons and a 55-year journalistic career, Lanciné Camara’s journey from Bélokoro to Paris is an enriching tale. After he engaged with African presidents and prominent figures who shaped his perspective, he is now driven by a desire to inspire the younger generation and leave behind a lasting legacy for African journalism.

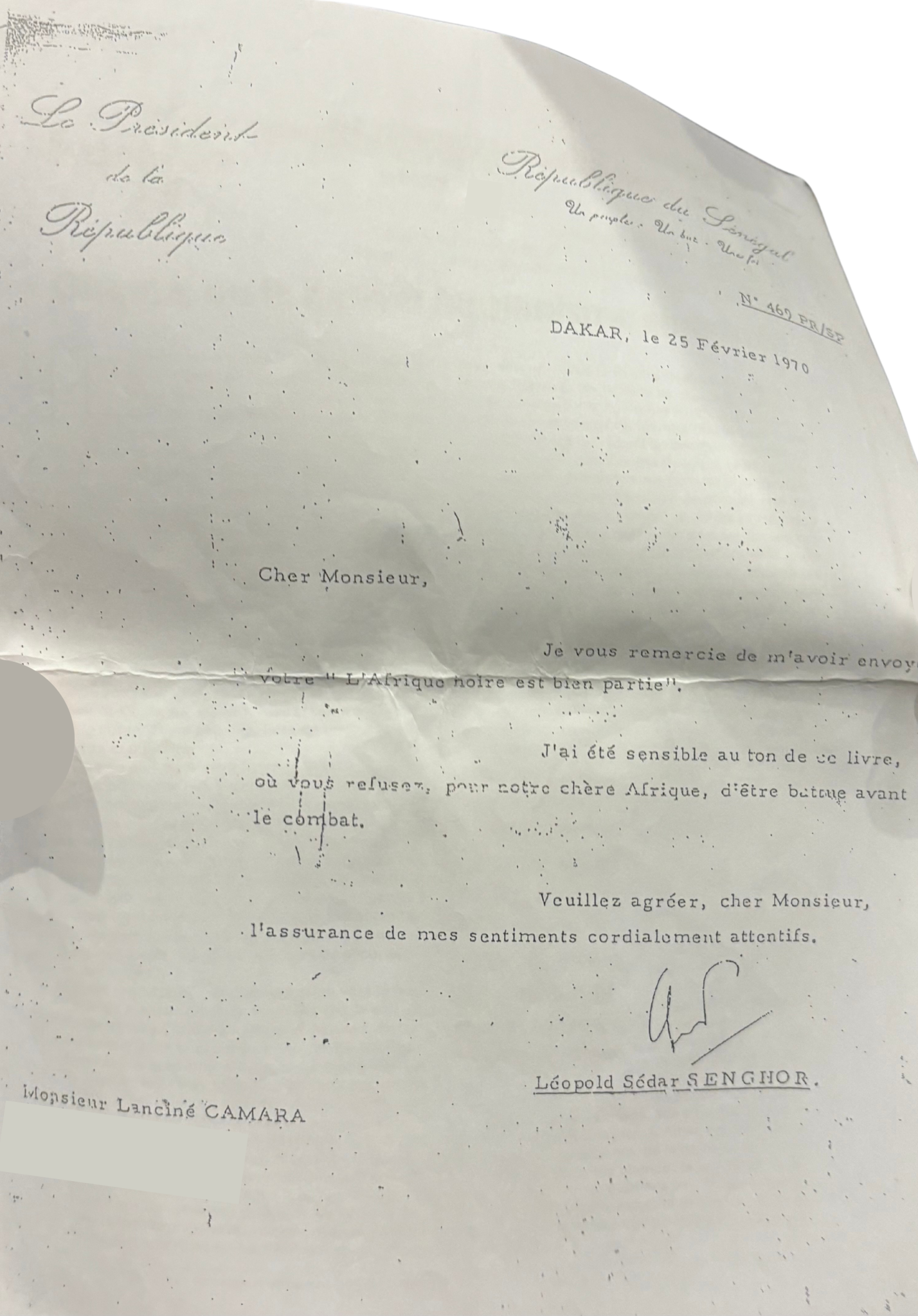

Dressed in a long green coat reminiscent of an investigator, Lanciné Camara, a Guinean journalist, carries within him supporting evidence of his journey. From a letter of admiration dated back to 1970 from the first Senegalese president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, to the DVD of the Miriam Makeba Prize from the International Union of African Journalists in 2023, Camara embodies a walking library, holding 55 years of journalistic career within him. Indeed, for Camara, a journalist must be “a surgeon of news, by speaking the truth and discerning falsehoods.”

As president of the International Union of African Journalists (UIJA) and founder of the monthly magazine Le Devoir Africain, Lanciné Camara, a journalist and writer with a repertoire of around a hundred articles, persists in his investigative endeavors focused on Africa and its diaspora.

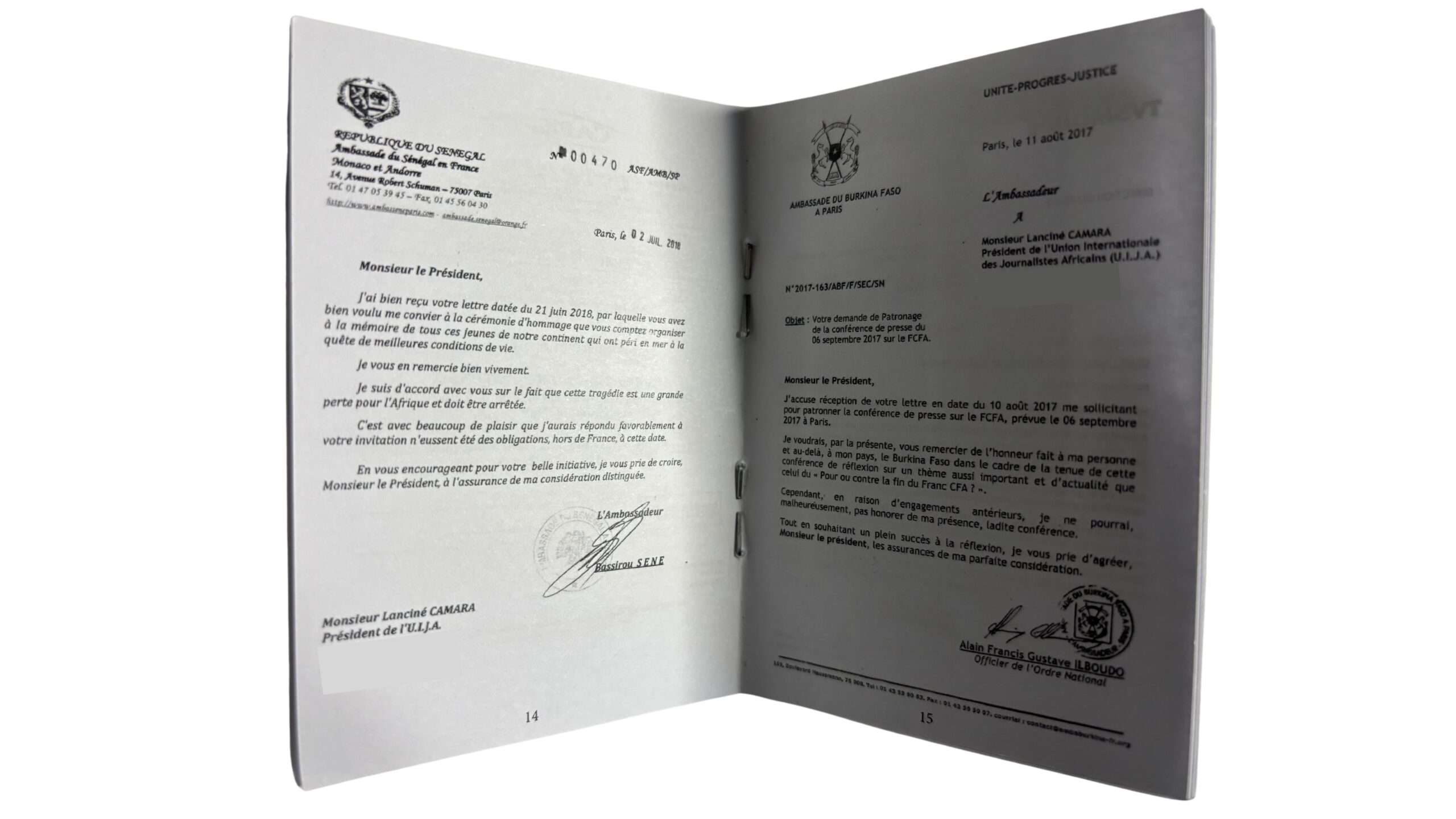

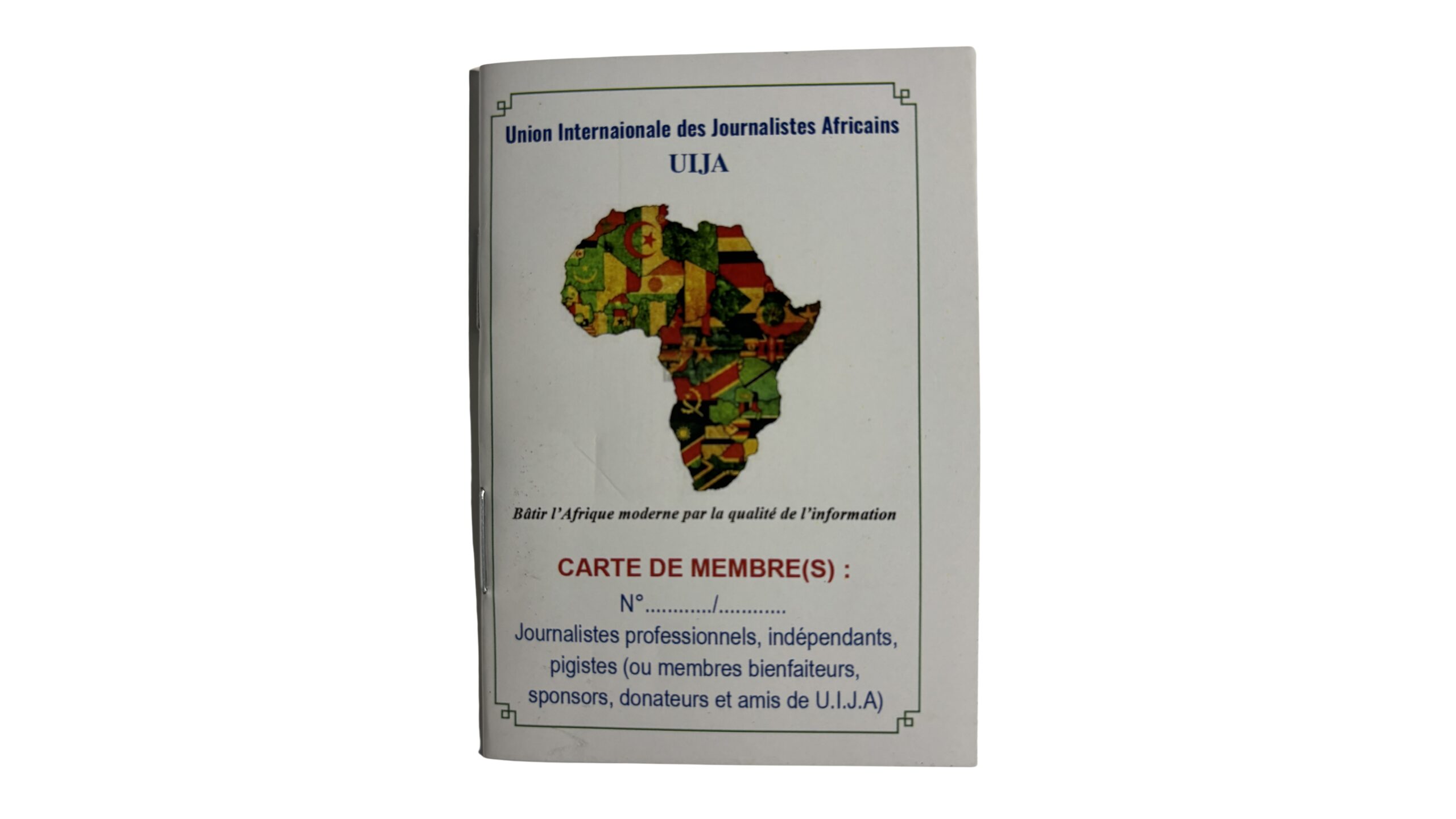

Simultaneously, he dedicates himself to mentoring the next generation of journalists, imparting insights into both the opportunities and challenges inherent in the profession. To substantiate his assertions and showcase the achievements of his NGO, Camara meticulously curates a collection of archives within a compact A8 UIJA booklet. These archives encompass a spectrum of materials, from invitations to press releases to responses received from African embassies or governments.

Hama Tandina Touré, aged 37, is one of the young journalists who work alongside Camara. Serving as a cameraman, editor, and the creative force behind the YouTube channel Afrika DiasporaTV, Touré expressed his admiration for Camara’s “structured” approach to their work. Following the filming of the presentation of the Miriam Makeba Trophy in 2023, Touré said it was one of the first times he saw “an African do something grandiose.”

“That’s different from what I usually see. Because we, West Africans, tend to be very minimalist. But Camara transcends those boundaries because when he undertakes a task, he always endeavors to achieve something monumental,” the 37-year-old cameraman added.

Lanciné, “The Librabry”

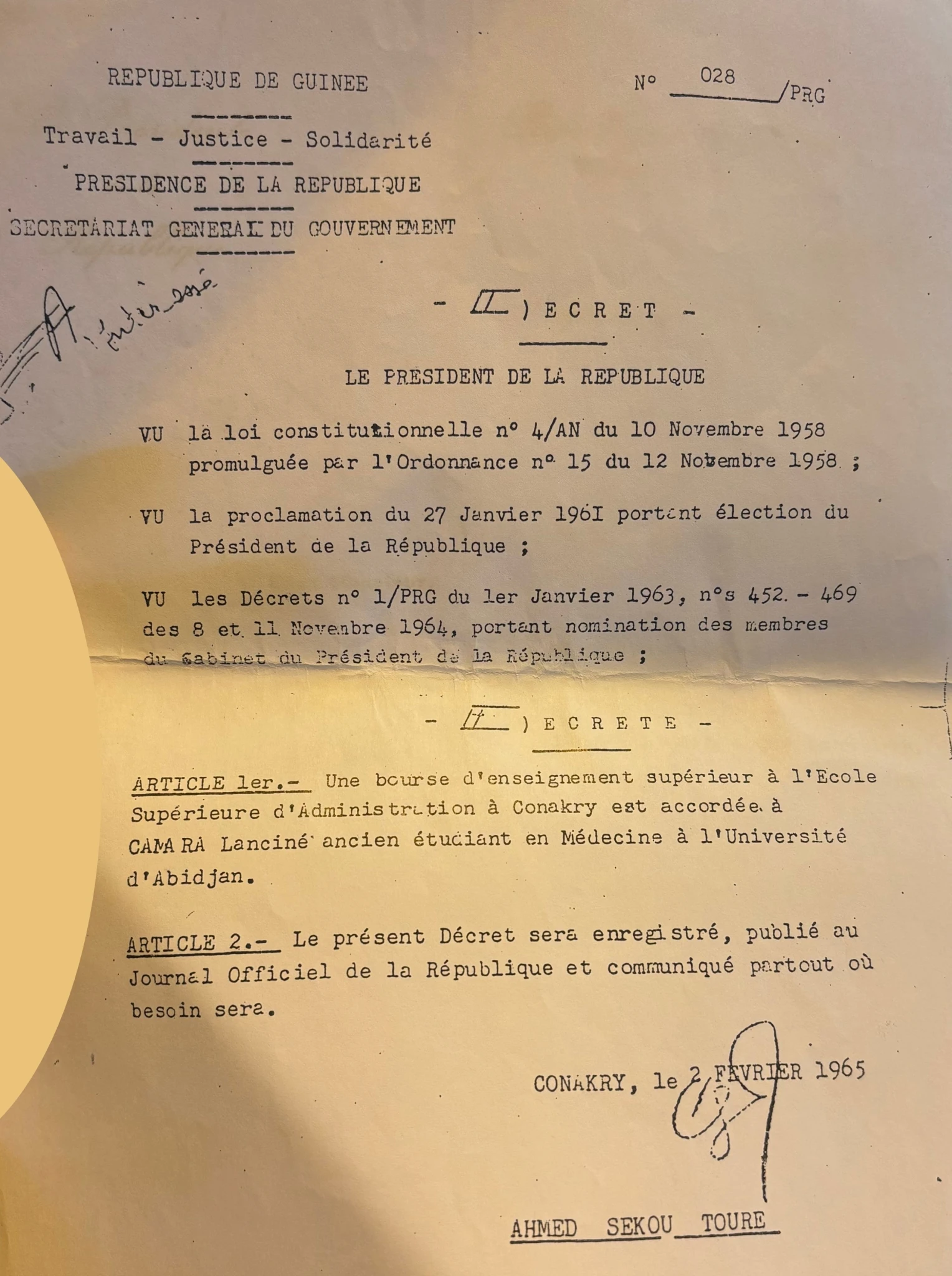

Lanciné Camara was born in January 1942, in Bélékoro, a small village in Beyla, southeastern Guinea Conakry. Initially, he wanted to become a doctor, leading him to commence his medical studies in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, in 1964.

However, Guinean President Ahmed Sékou Touré (1958-1984) issued a directive mandating that all Guinean students studying abroad return to their homeland, under the threat of potential loss of nationality. “I was directed to the School of Administration because they aimed for me to be one of the first thoroughly trained prefects tasked with defending the country’s interests,” said Camara.

But this directive from the former Guinean president isn’t the sole motive that led him to turn towards journalism. With eyes gleaming with admiration, Lanciné Camara fondly recalled his mother, whom he reverently referred to as his “first library.” Camara recounted how his mother, “a mother of six who toiled tirelessly in the fields,” placed paramount importance on providing her children with a “good education” as their legacy.

“At the time, she would tell me, ‘When I speak to you, you must listen. And when you listen well, you can convey messages more effectively.’ So, I always heeded my mother’s words. And I believe it was from there that I realized the profound significance of journalism – not only to listen to people but also as a vehicle to impart messages,” Camara said.

“One day, my older sisters and I asked my mother, ‘But why do you work all the time like this? You need to take a break,’ and my mother responded, ‘I consider myself fortunate to have escaped the horrors of the slave trade. Now that independence has arrived, I understand that by providing you with a solid education, I am investing in our collective future. If you succeed, it is not just for yourselves, but for the betterment of Africa.’ So, when people ask me, ‘How come you do all this at 82?’ I simply reply that it’s because your mother didn’t explain to you what mine explained to me. And for as long as I enjoy health, I will persist in the fight,” said the journalist.

An “Indefatigable” Journalist

Lanciné Camara arrived in Paris in 1966. Although regarded as “the dean of African journalists in France” by some, the 82-year-old journalist is preceded by Géraldine Faladé, a Beninese journalist and writer who formerly worked at Ocora Radio France, the precursor to Radio France Internationale.

From Senegalese author Cheikh Anta Diop to the Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verdean anti-colonial leader Amilcar Cabral, and from Cameroonian President Ahmadou Ahidjo (1960-1982) to Ivorian President Félix Houphouët Boigny(1960-1993), Camara has engaged in interviews and exchanges with prominent figures from the African political and cultural spheres. This includes encounters with Senegalese president Abdoulaye Wade (2000-2012), among others.

In 1970, Camara published ‘L’Afrique Noire est bien partie‘ (Black Africa Is Off to a Good Start) as a response to ‘L’Afrique Noire est mal partie‘ (Black Africa Is Off to a Good Start) (1962) by René Dumont. Camara’s retort elicited a written response from Senegalese President Senghor.

“When Senghor endorsed my book, I was overjoyed! Writing a book in opposition to figures like René Dumont was no easy task. They were revered as thought leaders of their time! Therefore, it required considerable courage for a young, relatively unknown individual like me to confront René Dumont!,” said Camara, his face beaming with a smile.

In 1982, Lanciné Camara interviewed Guinean President Ahmed Sekou Touré. “He even proposed that I accompany him back to Guinea. I declined because he would have cut off my head.”

While Camara has contributed to media outlets such as Bingo, Le Continent, Le Figaro, and Jeune Afrique, it was with Le Devoir Africain, established in 2000, that Camara found true fulfillment in his career. “I told myself, instead of working for others, I’ll work for myself,” said the journalist.

According to Touré, while Camara is described as “indefatigable,” he also demonstrates remarkable patience and willingness to support young individuals by extending invitations to various events.

Paving the Way for Young Journalists

With the rise of social media and artificial intelligence, Lanciné Camara perceives both a fresh wave of opportunities and challenges for young journalists. On one hand, the journalist underscores the importance for African youth to recognize the wealth of their continent, stressing that it’s not solely about “dancing and singing,” but also about “working.”

“We must educate the intelligentsia, creators, inventors, and all those who can contribute to Africa’s progress. While singing and dancing have their merits, Africa also needs an abundance of engineers, agronomists, doctors, and scientists. It is through this diversified workforce that Africa will truly advance,” said Camara.

On the contrary, Camara vehemently denounced the commercialization of journalism by major media outlets, decrying what he termed as ‘media colonization.’ According to the 82-year-old journalist, simply having a growing number of Afro-descendant journalists is insufficient; “they must also embody a sense of responsibility and awareness regarding their discourse.”

“I refuse to accept token representation in journalism, akin to those used to disparage the African continent. Regrettably, there are ‘house Negroes’ within the press. What I aspire to see is a Black journalist, whether African, Caribbean, or from elsewhere, who, when within any media outlet, regardless of its nature, upholds responsibility. They should elucidate matters not at the expense of their country or continent, but by articulating, ‘We acknowledge our responsibilities, yet it’s imperative to recognize yours as well’,” said Camara.

The journalist contends that commerce has obliterated ethics within journalism. “Journalism has become muddled since financial interests have taken over. For example, RFI is subsidized by the French state, thus tethering it to the defense of French interests exclusively! Ultimately, it reflects a desire to media-colonizethe continent, leveraging information to gain access to natural resources. I am apprehensive that journalism has devolved into a tool hindering the emancipation of nations in dire need.”

FeedSpot’s ranking of the top 45 African News Websites in 2024 was determined by factors including traffic, social media followership, and content freshness. Notably, a significant portion of the listed websites are headquartered in France, the UK, and the US, with fewer originating from African nations.

“One day, Gaddafi gathered us and said, ‘You, African journalists, what do you do when I am attacked like this? I tell you, organize yourselves, I am ready to finance you so that you can respond every time you are attacked. Because it’s your good leaders who are being attacked.’ That’s how we formed the UIJA within foreign associations, and since then, we have been defending Gaddafi, because there was no need to assassinate him. We could have even incarcerated him and allowed him to express his views. But that didn’t happen. He was eliminated so he wouldn’t have a chance to speak’,” said Lanciné Camara.

Today, Lanciné Camara believes that the youth have tools, like the Internet, that can help them move forward. However, the journalist warns the new generation not to allow themselves to be “mentally colonized.” According to Camara, “If from the start, you are mentally colonized, you won’t accomplish anything good. So, do not get discouraged, do not allow yourself to be bought nor manipulated.”