Anatomy of a Fall, Poor Things and Oppenheimer headlined the 96th Academy Awards ceremony, on 11th March, 2024. Better known as the Oscars, the institution has awarded the cinema productions for their excellence since 1929, through various categories such as the most prestigious one, Best Picture, which rewards the Best Film. But, do the prizes truly reflect the quality of a film? After the Oscars, how many prized films will remain in the minds? Will they become “classic films”? What exactly is a “classic film”? Three French experts, including one journalist and two academics, will allow us to go beyond the traditional frontier “I like”/ “I dislike” and to understand how the notion of classic film is constructed, before the Cannes Festival in May.

“Since the thirties, to define the best film has become a trade issue” says Jean-Marc Leveratto, professor of cultural sociology at the University of Lorraine and classic films specialist. Before the Oscars, some films benefit from an intensive marketing campaign by the production companies, revealing how the Hollywood machine works: lobbying.

The rankings: those who judge

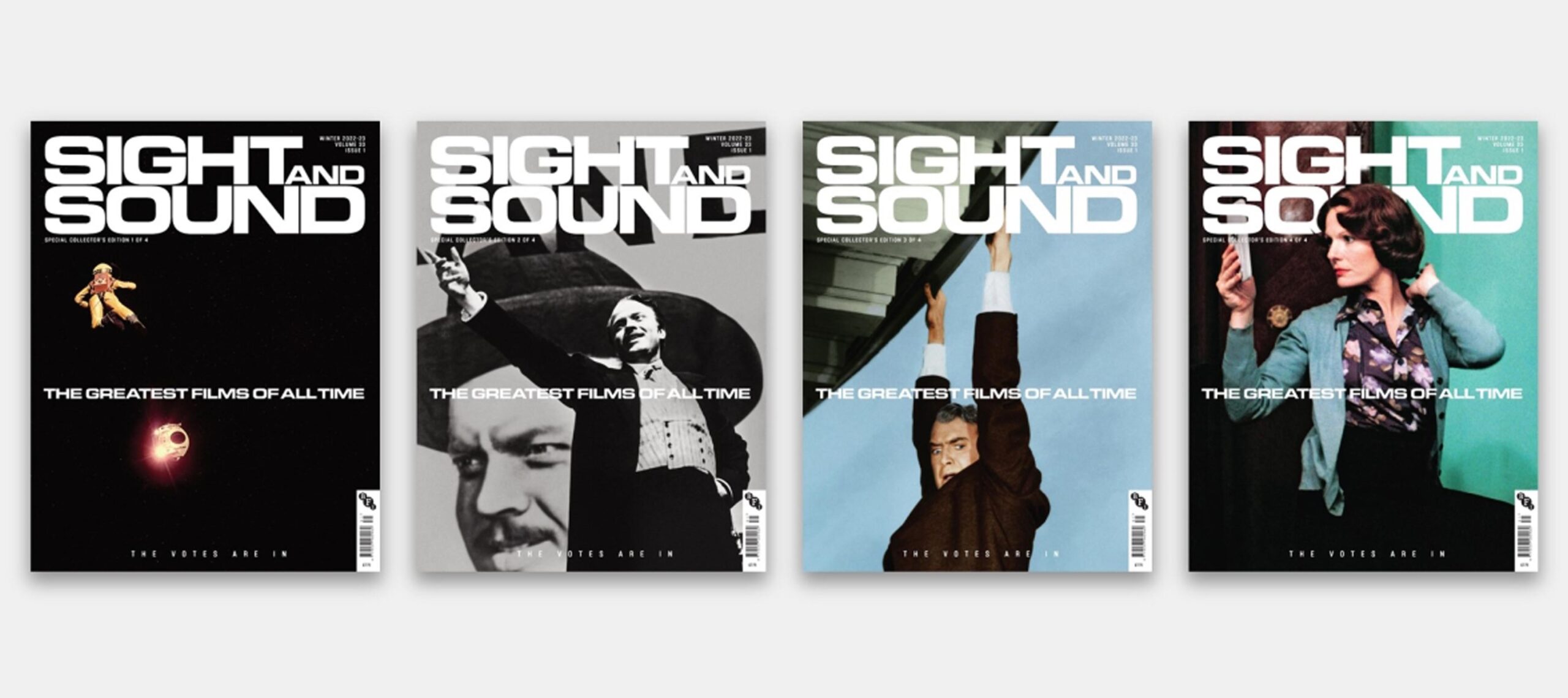

To label a film as the best legitimises it as such. The power of the institutions lies in the creation of a common list. For example, every decade, since 1952, Sight and Sound, a magazine published by the British Film Institute, conducts a poll of the Greatest Films of All Time.

According to Fabrice Montebello, professor of film studies at the University of Lorraine, the word “classic” comes from the Latin word classicus, that refers to the first-class citizens in ancient Rome. Its etymology is a social metaphor, which contains an elitist meaning. Over time, the word has been used to qualify what is the best in art. But how to define what is the best? The best needs to be known. This is why we study it in class. The value of a film may result from its formal perfection, its artistic quality, its age, its originality… The academic says:

The classic film stands out from the other productions […], it is intemporal, it can transcend borders of time and space.

But, who decides that a film is a masterpiece? At first sight, the notion of classic films seems to be an objective one. When the rules are imposed by specialised groups, the institutions and the film critics, the connexion with the public is broken. “We have the right to do not like a masterpiece” says Fabrice Montebello, because it is a matter of taste. We must not forget that the categorisation “good versus bad taste” can divide social classes. For our three experts, the classic film is characterised above all by an “immediate pleasure”.

In France, a particular type of meeting point takes the form of the film society, bringing together the experts and the general public, the cinephiles and the neophytes. The “ciné-club (in French) is the perfect place to watch a film for the one hundredth time or for the first time.

Echoes in the present

Through time, we found some fragments of films: they are common places, representing “what everybody knows, without necessarily knowing it” says Jean-Marc Leveratto. The line of Jean Gabin in Marcel Carné’s Port of Shadows (1938) – “You have beautiful eyes, do you know that?” – and the “chabadabada” from Claude Lelouch’s A man and a woman (1966), are still echoing in French minds.

“It is mostly the media environment which makes the classic film existing through snippets” asserts Charlotte Garson, deputy editor-in-chief at Les Cahiers du Cinéma, adding that “if it is a real classic, it does not need it, because a classic film is a global system”. At the same time, to remember only fragments of a film can destroy it.

About the music score for A man and a woman, composed by Francis Lai, Claude Lelouch said: “From the first notes, I recognize it. It’s like a song that we knew by heart for a long time, but that we forgot.” © IoniVision | Youtube

Some films can die, while others can reborn

If human beings are mortal, works of art can also have an expiration date. The generational renewal inevitably leads to a new definition of the classic films. However, Jean-Marc Leveratto notes that “Chaplin is one of the rare cases of a lasting transmission because parents still show it to their children”.

Films can lose some of their aura, especially when they represent only the era of their creation. According to Charlotte Garson, the main risk of this “time capsule” is that its signification froze. Then, it can become outdated.

At their release, some films have been criticised, with time, others have been forgotten. And one day, they have been rediscovered and have become classic films, when there is a consensus, or cult films, when there is a small group of passionate fans.

The Cinémathèque française offered a recent retrospective (2022) to the American director, Douglas Sirk. While his films were initially panned by critics, he is now recognised for its melodramas, as Imitation of Life (1959), which the opening credits – a shower of diamonds – are memorable. © Classic Movie Trailers | Youtube

“The artistic quality of a film does not preserve it from its disappearance” says Jean-Marc Leveratto, as shows the controversy about The Birth of a Nation (1915) by D. W. Griffith. He adds that “the perception of the past evolves with the present time”. According to Charlotte Garson, “there is an ethical dimension in aesthetic pleasure”, adding that:

Some films have the ability to update their meaning through time.

According to the journalist, “a true classic film still means something in the present time”. By matching with our current concerns and issues, it creates community.